Loo Foh Sang and the Persistence of Mastery by Zanita Anuar 卢伙生与精益的坚持

Loo Foh Sang and the Persistence of Mastery

By Zanita Anuar

Senior Curator, National Visual Arts Gallery

This article was published in “The Untiring Engraver” Original Prints by Loo

Foh Sang Exhibition Book in Year 2014, organised by Soka Gakkai Malaysia.

This exhibition is Master Loo Foh Sang’s seventieth birthday gift.

If we know the Master, this is more of his gift to us on his

birthday than SGM’s gift of granting a solo exhibition to him. This is ours to

enjoy and appreciate, more so it we have not already partaken of his brilliance

and mastery in printmaking before.

Art historians term the rejuvenated brilliance in the work of aged

artists as alterstiehl. This is

evident as seventy-year-old Master Loo’s latest works in this exhibition

emanate ever more interest in style and technique. Nonetheless, many who take

the time to gaze at the fine lines of Master Loo’s supreme drawing,

transference and innovation, will realise that the works are markedly superior.

There is no singular term of description.

It is that non-singularity that the oeuvre of Master Loo should be heralded.

As a curator I have always admired the refined craftsmanship and

sense of perseverance evident among print artists. The artists working in printmaking

must have a key understanding in the materiality of his tools and how it

affects his mark-making. Among the questions I ask myself is “How does a print

artist find the patience to produce art repetitively? Do they ever reach a

satiation point?”

Psychological studies on satiation by Sakurabayashi (1966) have

indicated that when one is forced to keep up a monotonous gesture (or

occupation), one tries to evade it not only by such devices as inattention or

forgetting but by varying the tasks.

I must admit that when one studies pre-existing prints, these

works can then be said to have differences. This becomes a creative device to

re-instate artistic identities as it overlays a much more subtle and

involutedly real differences: the differences can be noticed in gradients,

intensities, overlaps, and tints. It is the persistence of the Master

printmaker that will determine the best evolution.

In retrospect, it must be said that Master Loo’s mastery of art

was initially in painting. Mannerisms and strokes developed from the Nanyang

School in easel paintings later made way for the curiosity he held for printmaking.

It is in Paris that he developed great admiration for printmaking,

its tradition, technology and discipline. From 1967 to 1969, Master Loo then

studied and matured alongside a world-renowned maestro who is known to have

inspired Pablo Picasso, Alberto Giacometti, Joan Miró, Alexander Calder,

Marc Chagall, Jackson Pollock, and Mark Rothko.

The hiatus in his journey of learning was when he was accepted to

understudy printmaking under the tutelage of the maestro Stanley William Hayter

(December 27, 1901 – May 4, 1988), the English industrial chemist, printmaker

and painter who founded Atelier 17, known as the most influential print

workshop of the 20th century. In 1927, Hayter founded the legendary

Atelier 17 studio in Paris.

In his Preface to Hayter’s book published in 1949, New Ways of Gravure, printed by Oxford University

Press, Herbert Read introduced the author by stating:

Among contemporary artists, Stanley William Hayter has a wide

influence which is due to two distinctive features. In the first place he has

revived the workshp concept of the artist – the artist, not as a lone wolf

howling on the fringes of an indifferent society, but as a member of a group of

artists working together, pooling their ideas, communicating to one another

their discoveries and achievements. In the second place, he is an artist with a

philosophy, a philosophy that assigns a particular function to art in life, and

the artist in the life of society.

The master

introducing his late master at his studio during a recent interview with

author.

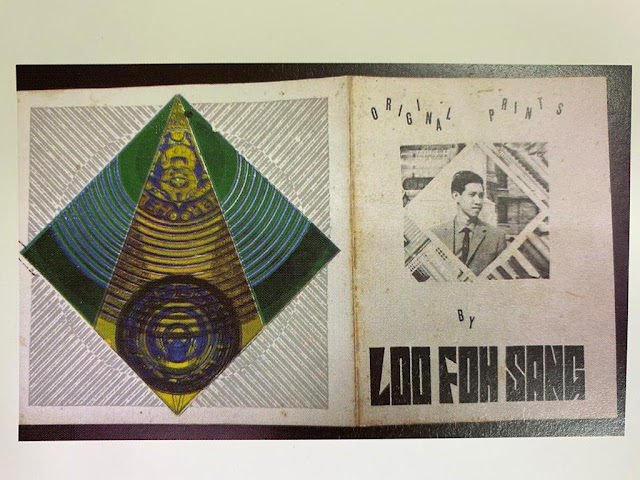

In the collection of works Master Loo developed in the Atelier, as

evidenced in his late 1960s exhibition catalogue “Original Prints by Loo Foh

Sang”, one can view a family of production emerging from working in the

presence of S.W. Hayter. Hayter is noted for his innovative work in the

development of viscosity printing (a process that exploits varying viscosities

of oil-based inks in laying three or more colours on a single intaglio plate).

Following Hayter, who termed this as “simultaneous printing” Master Loo

continued to produce and create innovative works.

Observing his early manifestations An Empty Hearted Woman, La Fete, and Composition produced in the

Atelier will undoubtedly illuminate our understanding of how printmaking propositions

have honed his level of attentiveness as it challenged him and will propel him

further in evolving print art and print art making.

The works in the exhibition held in Singapore, and commented by

the renowned Singaporean artist, curator and educator, Choy Weng Yang, were

mostly produced in the Atelier.

In all of Master Loo’s works, as evident in these early pieces and

more, modernism was not automatically in conflict with his own local tradition,

and the manner in which he exerted control throughout the picture-making

process, from the studio to printing, enables viewers today to derive an

understanding of his continuous re-examination of time, life and its

delicateness.

What elements are to be chosen and how they are placed, fixed and

connected are issues of great importance for the printmaker. The finality of

these smaller decisions is in turn registered in graphics that we see as a

finished picture.

The front cover of the catalogue accompanying the “Original Prints by Loo Foh Sang” Exhibition.

The aspects of the artist’s inner language of Eastern philosophy

and symbolist tradition become evident in Composition

III as he employs the Yin and Yang. The 1966 engraved works Composition 1 and 2 are displayed in the exhibition.

Composition III, 16.5 x 12cm, 1966

As the Australian sculptor, Bill Clements mentions in re-viewing

Master Loo’s “New Prints”:

In his

latest works, there are then the developed possibilities that colour allows in

alliance with an imagery that is drawn from his cultural heritage. And it is

the dialogue between these two elements that gives rise to images that speak of

an artist who has absorbed the influence of a master and has not become a clone

of that master. Any artist who works under the shadow of great trees must

eventually for the sake of feeling the warmth of the sun return to his sources.

And this is what Loo Foh Sang has done and done extremely well and

authentically.

In viewing the ensuing pictures and poring over the attributes

that are left by his print marks that make up his pictures, local attributes

such as the kite, the dance, the sway of kinetic rhythm are elegantly traced.

The Yin and Yang appears again in the Dance

de Ying et Yang, the intaglio pieces produced in 1981.

One will notice that in many of his Paris studio images, Master

Loo enjoys depicting fantasy and beguiling compositions which he further fuses

in a mist of colours. Summer Light (1972)

sees him producing the silvery and rainbow hued effect in intaglio using

just one roller. Vol en toute liberte, which

translates to “flight in complete freedom”, printed in 1982, is an arrangement of

a magically-nuanced white gold and silver vista.

Loo has devoted himself conscientiously to the art of printmaking.

He has lived in Paris until 1988, and returned home to teach printmaking at the

Malaysian Institute of Art until 1993. Subsequently, he was appointed Head of

Printmaking Department at the Central Academy of Art in Kuala Lumpur.

Master Loo has given great commitment in sharing the vocabulary of

print. The Malaysian art fraternity fondly recalls the annual exhibition of the

International Contemporary Prints at the Central Academy of Art. He is a

driving force for modern day printmaking in Malaysia. He organised, not one but

three Annual International Printmaking Exhibitions between the years 1996 to 1999.

This much anticipated event became the stage where hundreds of

international print artist from over 30 foreign countries including South

Africa, Germany, China, Turkey, USSR, Agentia, Bulgaria, India, Korea, Croatia,

Latvia, Japan, Indonesia and Singapore showed their mettle in printmaking

explorations. It was a loss for all when the annual exhibition discontinued

after three showings due to financial constraints and institutional

shortcomings. The art college that hosted this landmark print exhibition has

since ceased operation.

The absence of the most engaging print program at the turn of the millennium

was deeply felt and print art practitioners began to realise the loss, but not

in vain. The call of the ties actually pushed for further efforts in the

exploration of media and innovation by Malaysian Print Artists. Master Loo

thrived on with further experimentations and began work on paper cut intaglio

prints like the Moment of Flourish

series in the late 90s. One of which can also be seen in his optimistic 1999

work New Year Eve.

The years to follow saw the opening of printmaker studio residence

spaces like Juhari Said’s Akal di Ulu,

the Penang International Print Exhibition (PIPE) spearheaded by the Penang

State Museum and USM, the IN PRINT exhibition at the National Art Gallery and

several more initiatives.

In this exhibition, it can be discerned that this artist facility

with the medium of printmaking is expansive. In spite of the abundance of

methods and technology which provides for the ease of printmaking, he delves

into woodcut again. He conscientiously presses on with his knowledge of

tradition through his labour-intensive woodcut pieces of Dance and Sunset in 2000.

He individualises his sfumato

effects by experimenting with resin to deliver a soft ground effect as seen

in his Gamelan series. Although multiple figures may lead to issues relating to

composition, these can, at times, be dealt with by purposefully delineating

figures, carefully placed in picture planes so as to stimulate movement in

space.

Evidently, the Master’s best works are metal engraving, which he cut himself. This has often been said by other fellow artists whom I have approached*.

*Research for this exhibition

included the Master’s studio visit and casual interviews held with Jasmine Kok,

IIse Noor, Marvin Chan and Jamil Mat Isa.

The master, assisted

by apprentice artist Jasmine, sharing the etching plates produced for the dance

series.

However, it has been more importantly opined by a

discerning art critic, gallerist, collector and fellow print artist who is also

the former Director of National Art Gallery (now known as National Visual Arts

Gallery), the late Rahime Harun. In 2009, he mentioned that Loo’s original

prints were unique as they came from his rich experiences during his formative

years and his excellent training background. “The symbiosis of Eastern and

Western inclinations that has synthesised into Loo’s original style can be

attributed to the influences of Cheong Soo Pieng and S.W. Hayter.

“As an understudy with the two masters, Loo has in the

last 40 years, managed to emerge in the forefront of printmaking, each year

making great strides and exploring new techniques,” added Rahime.

The year 2006 is when his silkscreen of roses began to

debut. Bouquets of floral custers are created via his spoon-placement technique

of placing pigments. The highly deliberated arrangement creates a potpourri so

bold and vibrant.

Master Loo is undoubtedly one of the illustrious

Malaysian print makers of our times. He is among the finest draftsmen and an

artist of marked imagination and sensibility. As an informed print technician,

he raised the art of engraving to an admirable stature. As a machine innovator,

in 2011, he explores the creation of a different bed from which his prints

would arise and delves into perfecting plaster cast printmaking.

With a career spanning more than half a century, his

plaster cast prints, in addition to his lithographs, monoprints, engravings and

woodcuts, etchings and dry points, often reveal a series of rich relationships

between the vision and the spirit. His pursuit all these years is not only a

testimony of an aesthetic sojourn but also a continuous fortification of his

work ethics.

Resonating within Master Loo is the work ethics of a

great artist. In his continuous pursuit of perfection and nobility, he is

ever-inviting to share his knowledge. His decision to return to Malaysia despite

his successful sojourn in Paris was due to his pedagogic conscience. He was fueled by his mission to educate others as well as his vision to propagate a

deeper love and appreciation of printmaking.

The 70-year old Master Loo is planning his art museum. A

museum which is truly a print master’s abode within which is the printmaking

research studio, where he hopes to share with others the importance of

dedication, diligence and most importantly, the persistence of mastery, as one

thrives on in ascending the mediocre.

本文发表于2014年由马来西亚创价学会主办的卢伙生版画艺术展览“不倦的刻刀”的展览册。

由Zanita Anuar

国家视觉艺术馆高级策展人

本文发表于2014年由马来西亚创价学会主办的卢伙生版画艺术展览“不倦的刻刀”的展览册。

这次展览是卢伙生大师的70岁生日礼物。

如果我们认识这位版画大师,那么这不仅仅是SGM送给他的个展礼物,而是他生日那天送给我们的礼物。这是我们对他作品的欣赏与享受,更重要的是,学习他从没不放弃过他对版画的精通和精益。

艺术史学家将老年艺术家的作品中焕发的光彩称为“另类”。这很明显,因为七十岁的卢大师在这次展览中的最新作品引起了人们对风格和技术的越来越浓厚的兴趣。尽管如此,许多花些时间凝视卢大师的至高无上的绘画,转移和创新的精髓的人会意识到,这些作品显然是卓越的。没有单数形式的描述。

正是预示着卢大师作品的非奇异之处。

作为策展人,我一直很欣赏印刷艺术家中精湛的工艺和毅力。从事版画工作的艺术家必须对工具的重要性以及它如何影响他的标记制作有关键的了解。我问自己一个问题:“版画家如何发现耐心重复制作艺术品?他们有没有达到饱足感?”

Sakurabayashi(1966)对饱食的心理学研究表明,当人们被迫保持单调的手势(或职业)时,人们不仅试图通过注意力不集中或遗忘之类的手段来逃避它,而且还通过改变任务来逃避它。

我必须承认,当一个人研究已有的版画时,这些作品可以说是有差异的。由于它覆盖了更加微妙和渐进的真实差异,因此它成为恢复艺术身份的一种创新手段:差异可以通过渐变,强度,重叠和色彩来注意到。大师级版画家的毅力将决定最佳发展。

回想起来,必须说卢大师对艺术的掌握最初是在绘画中。南洋画派在画架绘画中发展出的举止和笔法后来被他对版画的好奇心所取代。

在巴黎,他对版画,其传统,技术和纪律产生了极大的钦佩。从1967年到1969年,卢大师随后与享誉世界的艺术大师一起学习并走向成熟,这位大师曾启发了毕加索,阿尔贝托·贾科梅蒂,琼·米罗,亚历山大·卡尔德,马克·夏加尔,杰克逊·波洛克和马克·罗斯科。

他在学习过程中的裂口是在斯坦利·威廉·海特(Stanley William Hayter)的指导下接受印刷专业的研究(1901年12月27日至1988年5月4日),他是创立Atelier

17的英国工业化学家,版画家和画家。是20世纪最具影响力的印刷工作室。

1927年,海特在巴黎创立了传奇的Atelier

17工作室。

赫伯特·雷德(Herbert Read)在牛津大学出版社出版的1949年海特著作的序言《凹版印刷的新方式》中,通过以下内容介绍了作者:

在当代艺术家中,斯坦利·威廉·海特(Stanley William Hayter)具有两个独特的特征,因此影响广泛。首先,他恢复了艺术家的工作能力概念-艺术家,不是作为孤独的狼在冷漠社会的边缘how叫,而是作为一群艺术家的成员,他们齐心协力,汇集思想,与一个人交流他们的发现和成就。其次,他是一位具有哲学思想的艺术家,一种赋予生活中的艺术特殊功能的哲学,以及一位社会生活中的艺术家。

这位大师在最近一次与作家的访谈中向其工作室介绍了已故大师。

卢大师在工作室开发的作品集中,如他在1960年代后期的展览目录“卢富桑的原创作品”中所证明的那样,人们可以看到在S.W.

W. S. W.的存在下工作所产生的一系列产品。海特。

Hayter因其在粘性印刷(该过程利用不同粘度的油基墨水在单个凹版上放置三种或更多种颜色的方法)开发方面的创新工作而闻名。继海特(Hayter)称其为“同时印刷”之后,卢大师(Master

Loo)继续制作和创作创新作品。

观察他的早期表现工作室生产的《空虚的女人》,《 La Fete》和《

Composition》无疑将阐明我们对版画命题如何提高他的专心程度的理解,因为这对他提出了挑战,并将推动他进一步发展版画艺术和版画艺术。

在新加坡举行的展览中的作品得到了新加坡著名艺术家,策展人和教育家赵卓的评论。

Choy Weng Yang,主要是在工作室生产的。

在卢大师的所有作品中,从早期和以后的作品中都可以明显看出,现代主义并不会自动与他自己的当地传统相抵触,而且他在从工作室到印刷的整个图像制作过程中施加控制的方式都可以实现。今天的观众对他不断地重新审视时间,生活及其微妙之处有所了解。

对于印刷商来说,要选择哪些元素以及如何放置,固定和连接它们是非常重要的问题。这些较小决策的最终性又被记录在图形中,我们将其视为完整图片。

目录的封面是“ Loo Foh Sang的原版印刷”展览的一部分。

当他聘请阴阳师时,他的东方哲学和象征主义传统内在语言的各个方面在《构图三》中变得显而易见。展览中展出了1966年雕刻的作品《构图1和2》。

构图III,16.5 x 12cm,1966年

作为澳大利亚雕塑家,比尔·克莱门茨(Bill Clements)在重新审视卢大师的“新版画”时提到:

在他的最新作品中,色彩的发展可能性与他从文化遗产中汲取的意象结合在一起。正是这两个元素之间的对话产生了一个图像,该图像表达的是一位画家,他吸收了一位大师的影响力,但并未成为该大师的克隆人。任何在大树的阴影下工作的艺术家最终都必须为了感觉到太阳的温暖回到他的来源。这就是卢伙生所做的事情,并且做得非常出色而且真实。

在查看随后的图片并仔细研究构成他的图片的印刷标记所留下的属性时,可以很好地追溯风筝,舞蹈,动感节奏等局部属性。阴和阳再次出现在1981年制作的凹版作品《舞蹈》中。

人们会注意到,在他的许多巴黎工作室图像中,卢大师都喜欢描绘幻想和迷人的构图,并进一步融合成一团色彩。 《夏日之光》(Summer Light,1972年)看到他仅用一个滚筒就可以在凹版印刷中产生银色和彩虹色的效果。

Vol en toute liberte译为“完全自由的飞行”,于1982年印制,是由魔术般的细微差别的白金和银景制成的。

卢大师专注于版画艺术。他一直居住在巴黎,直到1988年,然后回到家乡,在马来西亚艺术学院教版画,直到1993年。随后,他被任命为吉隆坡中央艺术学院版画系主任。

卢大师在分享印刷词汇方面做出了巨大的承诺。马来西亚艺术界热烈地回想起中央美术学院一年一度的国际当代版画展览。他是马来西亚现代版画的推动力。在1996年至1999年之间,他组织了三届年度国际版画展览,而不是一次。

这一备受期待的活动成为了舞台,来自南非,德国,中国,土耳其,苏联,阿蒂尼亚,保加利亚,印度,韩国,克罗地亚,拉脱维亚,日本,印度尼西亚和新加坡等30多个国家的数百名国际版画家展示了自己的才能在版画探索中。当年度展览在三场演出之后由于财政拮据和体制缺陷而中断时,这是所有人的损失。此后,举办此地标性画展的艺术学院已停止运营。

千禧年之际,人们缺乏最吸引人的印刷计划,这使人们深感不安,印刷艺术从业者开始意识到这种损失,但并非徒劳。这种联系的呼吁实际上推动了马来西亚版画家在媒体探索和创新方面的进一步努力。

Loo师傅继续进行进一步的试验,并开始制作像90年代后期的Moment

of Flourish系列之类的凹版纸印刷作品。在他1999年乐观的作品《除夕》中也可以看到其中之一。

随后的几年中,像Juhari Said的Akal di Ulu这样的版画工作室居住空间开放了,由槟州州立博物馆和USM牵头的槟城国际版画展览(PIPE),国家美术馆的IN

PRINT展览以及更多其他举措。

在这次展览中,可以看出,这种以版画为媒介的艺术家设施是广泛的。尽管有丰富的方法和技术可以简化版画制作,但他还是再次深入研究了木刻版画。他认真地通过2000年劳动密集型木刻作品《舞与日落》(Dance

and Sunset)继承了对传统的了解。

他通过对树脂进行实验以提供柔和的地面效果来个性化其sfumato效果,如他在Gamelan系列中所见。虽然可能导致多个数字对于与构图有关的问题,有时可以通过刻意放置在图片平面中的故意勾勒图形来处理,以刺激空间运动。

显然,卢大师最好的作品是他自己雕刻的金属雕刻。我接触过的其他同行艺术家经常这样说*。

*该展览的研究包括大师的工作室访问以及与茉莉花角,IIse Noor,Marvin

Chan和Jamil

Mat Isa进行的偶然访谈。

大师在学徒艺术家茉莉的协助下,分享了为舞蹈系列制作的蚀刻板。

然而,更重要的是,有远见的艺术评论家,画廊主,收藏家和版画艺术家也反对这一观点,他也是前国家美术馆(现称为国家视觉美术馆)的已故拉希姆·哈伦(Rahime Harun)。在2009年,他提到Loo的原始照片是独一无二的,这些照片源于他在成长初期的丰富经验和出色的培训背景。 “东方和西方倾向的共生已综合成为Loo的原始风格,这可以归因于Cheong Soo Pieng和S.W.海特。的影响。

Rahime补充说:“作为对这两位大师的研究,卢在过去的40年中一直站在版画制作的最前沿,每年都取得长足进步并探索新技术。”

2006年是他的玫瑰丝印开始崭露头角的一年。通过他的勺子放置颜料的放置技术,可以创建出花刺的花束。精心安排的花香营造出大胆而充满活力的花香。

卢大师无疑是当今马来西亚杰出的版画制家之一。他是最出色的制图员之一,并且是富有想象力和敏感性的艺术家。作为一位经验丰富的印刷技术人员,他将雕刻艺术提升到了令人钦佩的高度。作为机器创新者,他在2011年探索了另一张床的创作方式,从该床可以产生他的版画,并致力于完善石膏模型的版画制作。

他的职业生涯跨越了半个多世纪,他的石膏铸造版画,石版画,单色版画,版画和木刻,蚀刻版画和干燥点,经常揭示出视觉与精神之间的一系列丰富关系。这些年来,他的追求不仅是美学之旅的见证,而且是其职业道德的不断强化。

在卢大师内部引起共鸣的是一位伟大艺术家的职业道德。在不断追求完美和贵族的过程中,他一直在邀请分享他的知识。尽管他在巴黎成功定居,但他决定返回马来西亚的决定是由于他的教学良知。他的使命是教育他人,他的愿景是传播对印刷版图的更深的爱和欣赏,这使他倍受鼓舞。

现年70岁的卢大师正在计划他的美术馆。一个真正的印刷大师居所的博物馆是印刷研究工作室,他希望与其他人分享奉献,勤奋,最重要的是掌握的持久性的重要性,以此来提升平庸。

Comments

Post a Comment